“Pan’s Labyrinth,” directed by Guillermo del Toro, is a movie that blends together the harsh realities of post-Civil War Spain with a fantasy world. Released in 2006, the film introduces us to Ofelia, a young girl who, along with her pregnant mother, travels to the Spanish countryside to live with her stepfather, Captain Vidal, a brutal officer from the Francoist military.

Ofelia discovers an ancient labyrinth near her new home, and this labyrinth becomes a portal to a magical realm ruled by fantastical beings. The faun, a mystical and enigmatic creature, reveals to Ofelia that she is a reincarnated princess and must complete three challenging tasks to prove her identity and return to her magical kingdom.

As the young protagonist Ofelia navigates this treacherous world, she encounters the Pale Man, a grotesque creature seated at a sumptuous banquet table.

As Ofelia’s eyes are drawn to the tempting display of food, the fairies that accompany her act as her conscience, communicating a clear warning against indulging in the banquet. As Ofelia yields to her desires, snapping and consuming some grape, this seemingly innocent act sets in motion a series of events that lead to a horrifying turn of events.

The Pale Man, an embodiment of malevolence and strict adherence to rules, reacts to her transgression. His eyes, located in the palms of his hands, come alive, and he becomes a predatory force, seizing the opportunity to punish the intrusion into his domain. The fairies become victims of Ofelia’s lapse, falling prey to the Pale Man’s voracious appetite.

While the core of the movie is not about gender norms or food, it is interesting to note that in this segment, Ofelia takes the decision to eat grapes, rather than any of the other foodstuff present on the table. In that sense, she conforms to the pattern of women eating more fruit/vegetables/healthy overall. In contrast, the Pale Man devours the fairies (i.e., meat) in an act of aggression (Note that I am not suggesting that males are carnivorous crypto-fascists). The fact that there are important differences in diets by gender is in itself not controversial, either in scientific or popular discourses. The environmental implications are less explored (and more prone to heated debates). In this first article, I will paint the broad picture of what we know about these elements.

(I do not know whether eating fairies is environmentally sustainable however).

This article is part of a series. Click here to read the first article.

KEY TAKE-AWAYS

There are gender differences in food consumption, with some of them holding true across cultures (e.g., males tend to consume more meat)

It is complex to assess the environmental impacts of food consumption due to methodological limitations, heterogeneities in agricultural practices and scope of considered impacts.

Existing studies suggest that men tend to have higher environmental impacts due to their food consumption then women. It is especially the case for greenhouse gas emissions, and tend to be linked to quantities consumed but also to the composition of diet (e.g., disparities in meat preferences).

Several factors can explain these differences, including biological, psychological and social ones. Decomposing the causes is challenging (and may not be fully possible/meaningful).

France was not covered in existing analyses of environmental impacts of food consumption by gender (at least no dedicated studies were retrieved in this project).

From the extremes to the mainstream: gender differences in food consumption

Try to picture extreme eating habits. Someone who is anorexic? Probably a girl/woman. Someone who eats as many hot-dogs as possible in a competition? Probably a man.

These stereotypes tend to be confirmed by evidence, at both ends of the spectrum1See e.g., Wansink et al. (2016) for competitive eating. The US Institute of Mental Health documents anorexia rates twice as high in females as in males in America, though there may be some underdiagnosis in men2See NIH.

But the intrigue does not end there! While there are obviously some differences depending on the places, time periods and contexts, the current evidence leads to a series of stylized facts, that largely hold between different cultures:

- Women often lean towards a diet rich in fruits and vegetables.

- Men, on the flip side, show a penchant for meat, processed foods, fats, and a touch of alcohol.

- Women tend to align more closely with dietary and health recommendations.

- Additionally, women exhibit a heightened awareness of the environmental impact of food (evident in studies like the Cantaragiu study on a small Romanian sample and reviews by Sanchez-Sabate et al.)

This situation is caused by multiple factors that interact in complex ways, as documented in a recent review of the literature by Grzymisławska et al. (2020): “eating behavior, food choice and nutritional strategy which were conditioned by evolution and by intra-individual (biological or psychological) and extra-individual (socioeconomic and cultural) factors”.

But what does it mean for the environment?

Despite some uncertainties, males are generally believed to have a greater environmental impact from their food habits than women

Estimating the environmental impacts of food consumption is a complex task due to several factors, including the limits of the deployed methodologies, measurement issues, and heterogeneities across different agricultural systems. When dealing with the consumption of food, additional issues emerge when compared to production: assumptions related to behaviors (e.g. food waste at home3UN studies showed that food waste at home typically reached 17% of food production at the global level ).

Different approaches can be used to assess the environmental impacts of food. The most popular is probably the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which consider the impacts throughout the entire life cycle of foodstuff; including production, processing, transformation and consumption. However, the choice of system boundaries (defining what is taking into consideration in the analysis and what is excluded) and data sources can vary, affecting the accuracy of results4For a recent review, see e.g., Nemecek et al. (2016).

Agriculture is diverse, with a wide range of production systems and practices. Crops, livestock, and farming methods differ globally, leading to variations in environmental impacts. Setting a “representative” impact can thus be difficult.

The types of impacts being considered also tend to vary. Typically, it is easier to analyze the carbon impact of food production and thus its contribution to climate change. Other aspects (such as impacts on biodiversity) can be more challenging to measure, and are thus less explored in research at this stage.

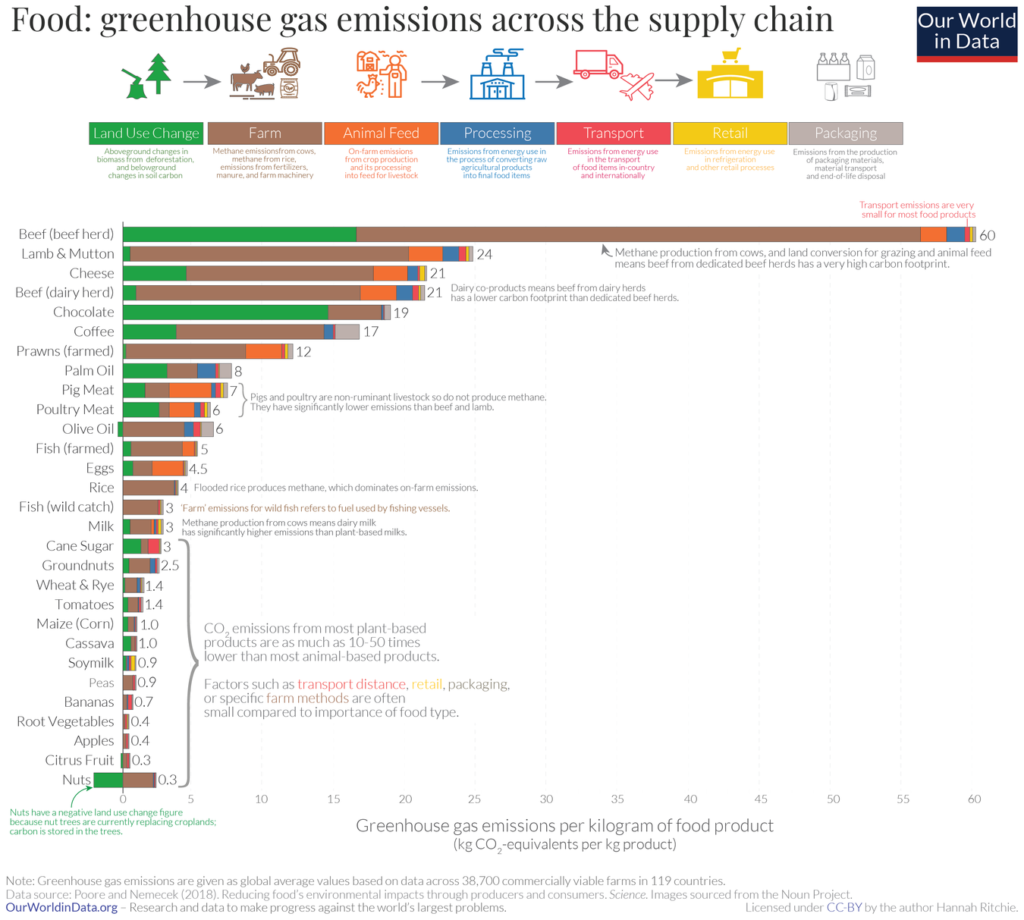

In spite of these limitations, the literature still managed to derive some key insights that seem to hold water5see Ritchie et al. and Nemecek et al. (2016) from an environmental point of view:

- Food production account for a significant share of the total environmental impacts of human activities

- Agricultural production often dominates the environmental impacts of food consumption, but its importance depends on multiple factors (types of products, production mode…)

- Meat (and dairy…) leads to important environmental impacts, and healthier diets tend to lead to reduced environmental damage

Existing studies also insist on two common misconceptions: locally-sourced food and organic farming. Indeed, these methods are not universally better for the environment than alternatives, though they can have pros and cons.

In particular, local food often fails to improve the environmental impacts of consumption because transportation typically only contributes to a small share of the impacts (when compared to production per se)6This was comprehensively studied for climate change, but is likely true for several other environmental impacts as well (e.g., biodiversity pressures that are linked to land use also have important climate effects).. Long-range transportation (e.g., in container ships) is also much more environmentally efficient than last-mile transportation.

Still, Impacts can however be important for foodstuff that require air transportation (e.g., some tropical fruits, asparagus…). Local food can also be a reasonable heuristic for some differences in agricultural practices (e.g., pesticide use, quality controls…).

For organic farming, the issue is also characterized by important heterogeneities depending on the type of food, exact conventional and organic practices and types of impacts. According to one of the most comprehensive studies so far7Clark and Tilman (2017) based on 742 agricultural systems and 90 unique foods, conventional farming performs clearly better for land use 8a significant factor of climate change and biodiversity impacts, while organic farming typically fares better for energy use. Other impacts tend to be more mixed.

So, while organic farming can have valuable benefits (especially when the gap in yield is low with respect to conventional practices), it is not a silver bullet for the environment.

With all these caveats in mind, a few studies tried to link the environmental impacts of food consumption to gender differences. Actually, I was surprised by the fact that I only managed to find such a limited number of studies attempting that. Indeed, I managed to retrieve four recent studies, two on Germans, one on Brits and one on Swedes. I assume there might be some analyses on gender differences in more “generalist” publications (e.g., for the USA…). If you are aware of additional evidence, please mention it in the comment section. It seems that the study on Swedes by Kanyama et al. got the most media exposure 9for instance in the Guardian.

The existing studies follow slightly different approaches and do not target the same populations and impacts. The studies are summarized in the following table:

| Study name | Authors | Year | Population | Methodology | Studied Impacts | Key results |

| Environmental Impacts of Dietary Recommendations and Dietary styles: Germany As an Example | Meier et al. | 2012 | (Partially) Representative data on food intake from National Nutrition Surveys (2006 and 1985-89 data). 25,000 persons (age 4-94) for West Germany in 1985-89; 19,000 persons (age 14-80) for reunified Germany in 2006. | Input-output LCA / hybrid-LCA for the environmental impacts (intake amounts converted to food supply and then to impacts) Beverages (alcohol, tea coffee…) excluded from the analysis | Climate change, ammonia emissions, land use, blue water use, phosphorus use, primary energy use (impacts based on a standardized energy intake of 2000 kcal per person per day) Cradle-to-store (no analysis of food preparation or waste at home) | Female diets are generally more sustainable than male diets when measured on a standardized 2,000 kcal per person per day basis. This holds true for all studied impacts, except for blue water usage. |

| Dietary climate impact: Contribution of foods and dietary patterns by gender and age in a Swedish population | Hallstrom et al. | 2021 | Swedish cohorts, nationally representative of women and men in the age group 56-95: 25,540 women (Swedish Mammography Cohort), 26,578 men (Cohort of Swedish Men) | Self-administered questionnaire on dietary information (2009 data). Matched with LCA on climate impacts for Sweden | Climate change only, farm to fork (also distinguishing impacts per quantity and per energy consumed) | The average yearly impact is 2.0 tons of CO2e per person. Men had a 36% higher climate impact from food consumption compared to women, primarily due to greater average energy intake. |

| Shifting expenditure on food, holidays, and furnishings could lower greenhouse gas emissions by almost 40% | Kanyama et al. | 2021 | Units from the households expenditure survey of Sweden (2016), i.e., 2,871 households, average single man household (369), average single woman household (251) | Hybrid method combining input output data and process analysis. Impacts are expressed per monetary unit. Non-food expenditure is covered Carbon intensities were matched to the expenditure patterns of the studied populations. | Climate change (greenhouse gas emissions) | In 2016, women had a slightly higher greenhouse gas impact than men, largely due to greater dairy consumption (men consumed more meat). However, future projections suggest that women will likely have a lower impact than men. |

| Variations in greenhouse gas emissions of individual diets: Associations between the greenhouse gas emissions and nutrient intake in the United Kingdom | Rippin et al. | 2021 | 212 adults | Automated online dietary assessment for the sample (three days) Linkages between food climate impacts (LCA), the composition of consumption and dietary data | Climate change (greenhouse gas emissions) Analysis performed at the level of precise food stuff (over 3,000) Analysis from production to retail | Men’s greenhouse gas emissions were 41% higher than those of women. |

Findings were thus somewhat heterogeneous, but they tended to agree that men had higher environmental impacts due to food consumption then men (with the exception of Kanyama et al. on Swedes, which had a slightly different approach – based on the carbon intensity of expenditure). Potential controls (e.g., due to different height / energy needs by gender) can also complexify the picture.

An area of agreement was also the fact that meat had a gendered consumption pattern, and that it was this area that typically created an imbalance in male impacts.

Also, nothing for France! The idea of this project is thus to investigate what’s the situation in this country, and to cover a wide range of environmental impacts. These previous studies would constitute good benchmark to check / contextualise our results.

Notes

- 1See e.g., Wansink et al. (2016) for competitive eating

- 2See NIH

- 3UN studies showed that food waste at home typically reached 17% of food production at the global level

- 4For a recent review, see e.g., Nemecek et al. (2016)

- 5see Ritchie et al. and Nemecek et al. (2016)

- 6This was comprehensively studied for climate change, but is likely true for several other environmental impacts as well (e.g., biodiversity pressures that are linked to land use also have important climate effects).

- 7Clark and Tilman (2017) based on 742 agricultural systems and 90 unique foods

- 8a significant factor of climate change and biodiversity impacts

- 9for instance in the Guardian